In an unexpected turn of events, the DC Circuit independently decided that the entire circuit court panel (11 judges) should hear the challenge to Obama’s carbon rule. The practical effect is that oral argument will delayed from June 2 until late September. For all intents and purposes, this is positive news for the challengers and should encourage states to safely put their pencils down if they haven’t already.

Initially, both sides had viewed expedited review of the case positively. The petitioners saw it as a backup in the event they did not receive the stay, effectively trying to minimize any harm done while the courts were reviewing the regulation. The EPA likely viewed the expedited process as a “free consolation prize” to the states in exchange for the court denying the stay request. Once the Supreme Court granted the stay, however, the challengers’ reason for seeking expedited review no longer existed.

Of course proponents of the rule argue that this “streamlines the path to the Supreme Court” since there was the potential for en banc review in addition to the three judge panel. Given the heavily Democratic composition of the DC Circuit and favorable panel EPA drew with the three-judge panel, it is just as likely that the case would have been appealed straight to the Supreme Court anyway.

EPA might have lost six months or more

The new timeline for resolution is likely slowed down by a few months and potentially even six or more months depending on the losing party’s appeals strategy. Instead of a likely petition for Supreme Court review in the Fall with oral arguments and decision in the late Spring, the request for Supreme Court review may not arrive until Spring 2017. This could easily push oral arguments to the Fall 2017 with a decision not issued until 2018.

DC Circuit presents more opportunity for dispute

The road also got more difficult for the EPA. No one doubted the favorability of the three-judge panel to EPA’s position. Now, it must convince five DC Circuit judges of their regulation’s legal merits, rather than two. True, both panels would possess a majority of Democratic appointees. The larger panel, however, will not be as favorable to EPA as they might have hoped with two liberal judges recusing themselves – one of which is currently nominated by the President to fill Justice Scalia’s vacancy (EPA proponent Merrick Garland). This leaves a delicate 5-4 balance of Democratic and Republican appointees hearing the full court challenge.

More than a case of agency deference

The court’s sua sponte decision to move immediately to en banc review also indicates the court’s assessment that the case is not a simple matter of agency deference. As the court of first appeal for Clean Air Act challenges, the DC Circuit is traditionally keen on adherence to established administrative procedure. Yet, the EPA’s unusual (and last-minute) revised interpretation of a key Clean Air Act provision – whether their mercury rule under Section 112 prevents them from regulating the same power plants under Section 111 – is an obvious vulnerability for the agency. The abnormal litigation strategy raises questions of arbitrary and capricious agency action and outcome-oriented interpretation.

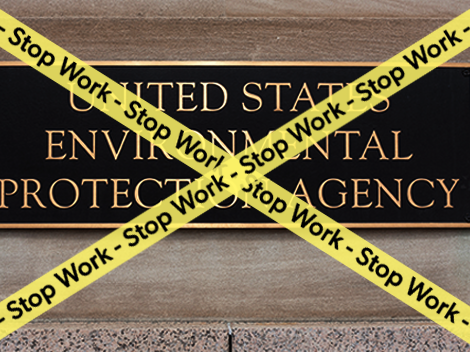

Signal to states: Wait and see

The takeaway for states is even clearer than before. Resolution of this case will not occur until later 2017 at the earliest, when a full Supreme Court is able to hear the case. The November election will certainly influence the Court’s composition but even assuming the rule is upheld by a Clinton Supreme Court, states will not face any obligations until well into 2018. Additionally, as is customary with litigation on complex regulations, further agency action on the rule such as revising timelines, updating underlying assumptions, and even modifying state requirements is quite likely even if upheld. This means states continuing work now face tremendous uncertainty. The wise course of action would be to stop work until more clarity is provided. Perhaps they could even focus on prioritizing affordable energy in the meantime.